A Caste in Cloth

Purple has a long and rich history (pun intended).

The history of the origin of purple-dyed fabrics and clothing is tied to economics. It is, in short, a narrative of wealth and class.

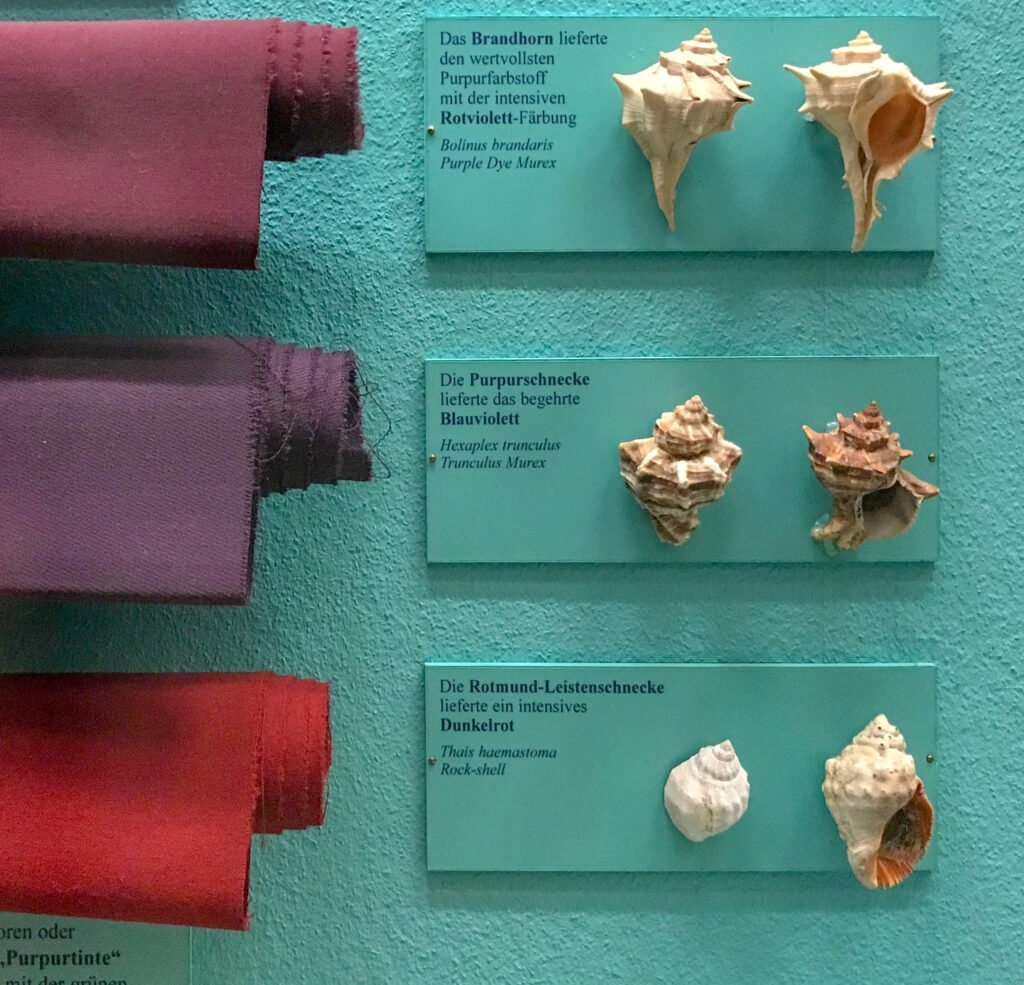

Historically, purple was a very difficult color to manufacture naturally. It was first manufactured in the 16th century B.C.E., in the ancient coastal city of Tyre in the region of Phoenicia (modern-day Lebanon). And it all originates from a snail!

I know you might be thinking to yourself, “Well, what about purple flowers or berries?” I thought about that too. However, the Spiny Dye-Murex snail’s purple-y mucus was a more reliable source to make purple dye when taking into consideration factors of vibrance, adherence, and lifespan after multiple rounds of washing.

SOURCE: Original photography by U.Name.Me, retouching by TeKaBe. (CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED)

Hercules’ Fated Date on the Beach

Here is a fun mythological anecdote about the origin of purple, as recorded by Julius Pollux dated in the 2nd century C.E.:

Hercules and his dog were enjoying a nice, long walk on the beach when his dog ate a sea snail and began to drool purple. That’s how the Phoenicians learned how to create purple cloth.

In the Tyrian tradition of the time, Hercules was associated with the Phoenician god Melqart, and so it is sometimes this character who appears in the purple dye myth.

Large amounts of this mucus would be needed to yield even just an ounce of dye. Due to this difficulty in production, it became a symbol of wealth and status—simple supply and demand logic. The only individuals able to afford purple-dyed fabrics and clothing were royalty (think kings and emperors), the rich, the aristocracy—basically, those with wealth or who had a high status.

Since only those of wealth and status were wearing purple clothing, this social norm blossomed into a physical narrative. Purple equals wealth and status, and thus, those wearing purple are wealthy and/or have a high status.

Oh, to be ‘Born in Purple’

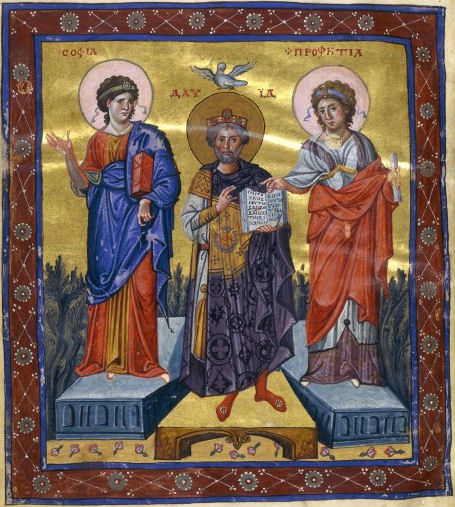

The Byzantine Empire is particularly known for their adornment of purple. Leaders and children of high-ranking families in the Byzantine Empire were considered to be born in purple.

What does this mean? One of two things. Either children were born to parents that were adorned by the mark of purple (only those of wealth and status had the legal and economic ability to wear purple clothing through sumptuary laws) or they were born in the porphyry chamber in the Great Palace of Constantinople, which was a cubicle room with nearly every square inch covered with purple porphyry stone.

Because of the scarcity of purple dye, to be born in purple held the narrative of being born into wealth and status.

SOURCE: National Library of France

SOURCE: Detail from a Greek manuscript dated 879-883 AD and containing the homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus, now in the National Library of France. (CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED)

It didn’t take long for these social norms around royalty, wealth, and status to become institutionalized—and they traveled far and wide.

For example, Queen Elizabeth I of England enforced her “sumptuary laws” in the late 1500s, which prevented people from purchasing and wearing purple clothes. Thus, purple was not only restricted socio-economically, but also legally.

What are sumptuary laws?

Sumptuary laws are laws that are “designed to restrict excessive personal expenditures in the interest of preventing extravagance and luxury” (Britannica).

In essence, they are laws that often restrict the masses; they are not only discriminatory, but also hypocritical. Thankfully, however, these laws are difficult to enforce and oftentimes ignored.

The Queen had strict laws on what English High Society could and could not wear, from certain fabrics to certain colors. And, yes, you guessed right, this included purple. Only relatives and close friends were legally allowed to wear purple. Although sumptuary laws are understood to restrict luxury and excess, this of course did not apply to the crown or their closest confidants. The punishment for not following the sumptuary laws would be a fine, or, if one did not have the money to pay the fine, jail time. Thus, purple became a caste in cloth in English society.

Enter William Henry Perkin, an English chemist. While “trying to synthesise quinine, a Victorian anti-malarial,” Perkin discovered a way to synthetically produce purple dye. This was about three hundred years after Queen Elizabeth’s sumptuary laws were first introduced. Perkin patented the color and named it “mauve” after the French purple flower mallow.

PHOTO CREDIT: Rouibi Dhia Eddine Nadjm (CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED).

Following the rules of supply and demand logic, here’s a question for you! What would happen if something scarce and seen as high quality all of a sudden became easily producible and accessible? Answer: it no longer becomes as desirable.

One could say this was the beginning of the end for this particular physical narrative of purple. Mass production and access to purple no matter one’s socio-economic status broke down purple’s narrative of wealth and status.

Gosh darn supply and demand!

WHERE TO NEXT?

Of Gods, Myths, and (Holy) Spirits

IMAGE: Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz presides over an observance of All Souls’ Day at the John Paul II Sanctuary in Krakow on November 11, 2018. (Photo by Joanna Adamik for the Archdiocese of Krakow.)

A “Pop” of Culture (and Color)

A museum patron admires some of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies paintings in the Musée de l’Orangerie. (PHOTO CREDIT: Adrian Scottow [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

The Politics of Purple

British actress and producer Lillie Langtry. (SOURCE: Langtry illustration by Herbert Gustave Schmalz , circa 1900)