Back to “Michel Foucault” Homepage

A Journey into Foucault’s Ideas

Now I’d like to take you through a more interactive means to understanding Foucault.

As I myself learned more about his ideas, I found that creating visuals or media elements helped me piece together the connections between some of his works and theories.

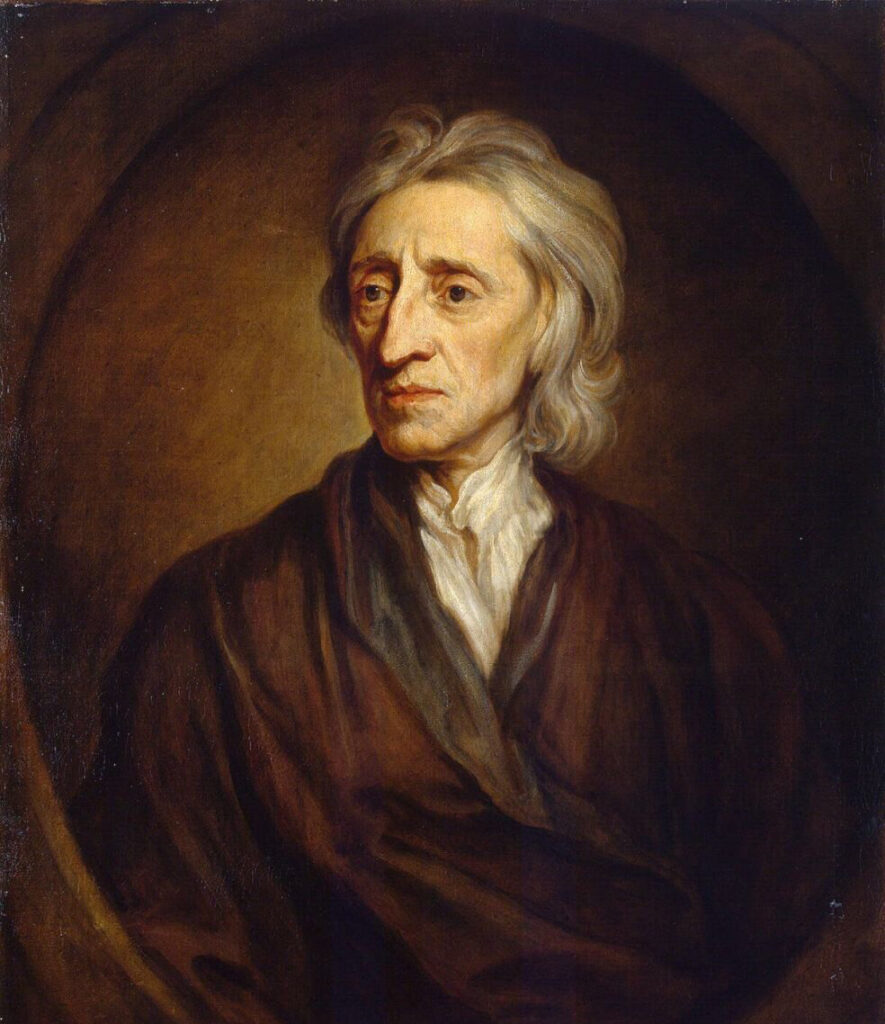

For example, as I considered the systems reflected in Discipline and Punish, I put together the following venn diagram as a great way to represent them:

(May not be re-used, copied, distributed, or remixed without prior permission from the author.)

Schools, prisons, and mental asylums are just some of the institutions where disciplinary power operates, but all hint at a larger idea of how power overlaps and is embedded throughout multiple spaces.

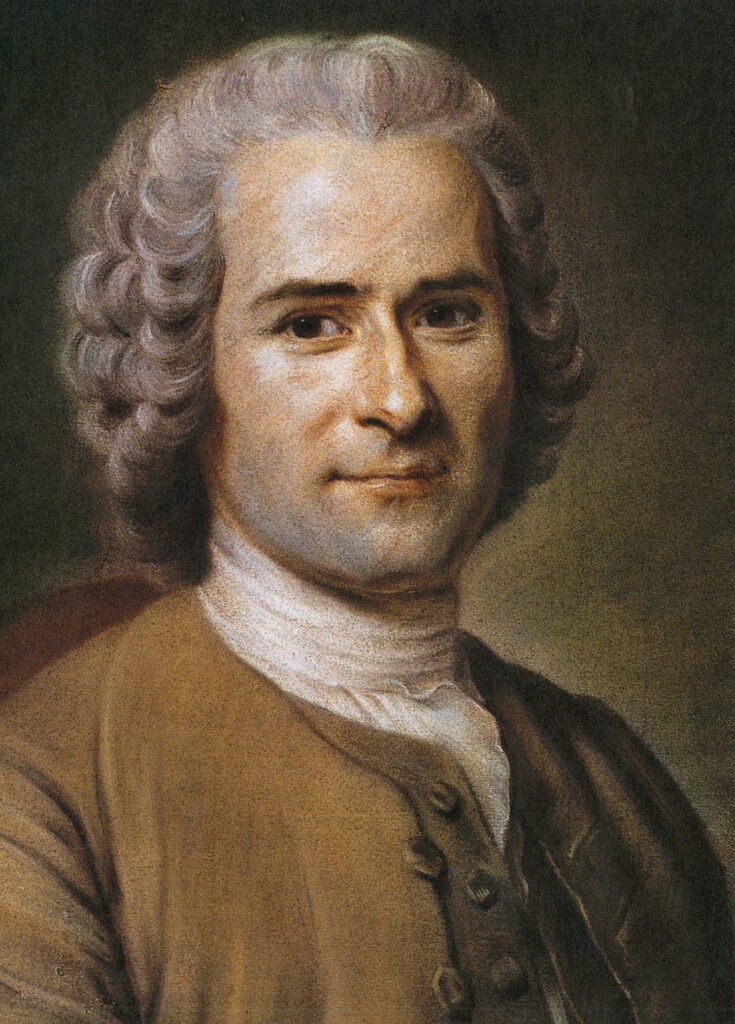

When I think about this, the first visual that comes to mind is a web. Foucault has a clever piece of imagery that displays the interconnectedness of these forms of power really well. He calls this capillary power, or how power operates at every social level!

(May not be re-used, copied, distributed, or remixed without prior permission from the author.)

Whether you believe it or not, there’s always some power dynamic existing in every action surrounding you—not just in big things like war or the healthcare sector, but in smaller things too, like classroom size or even bus stop locations. 🤯

But how do more “official” institutions fit into this picture?

As you’ve seen in the segment of the video on archeology vs. genealogy I attached in the first part of this rabbit hole, Foucault addresses these institutions via the concept of governmentality. Governmentality describes how people intentionally participate in regulating their own conduct on a population-based level. It indicates a more deliberate or purposeful means of organizing a body of people.

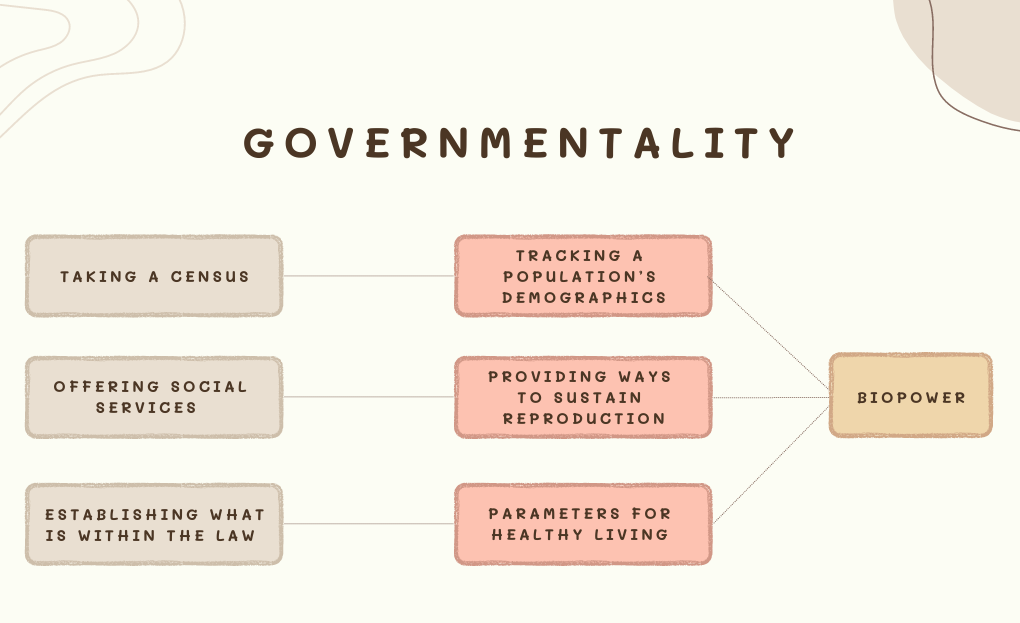

Some examples of this include:

- Taking a census

- Providing services like housing assistance or public education

- Instituting legal procedures

While you’re reading this list, you might be thinking that the above all sound pretty standard. Nothing exactly jumps out as a use of power, or something regulatory. But take a look at what these examples have in common:

(May not be re-used, copied, distributed, or remixed without prior permission from the author.)

Looking at this graphic, we have the initial bullet points or actions on the left. But as we think about what each point does, we see added nuance that leads to one commonality: biopower.

As Foucault developed his concept of governmentality, he considered the various means through which people would govern themselves. Unlike disciplinary power, which functions on a more individual level, biopower describes policies that organize and shape biological aspects of life, from reproduction to death to quality of life.

What’s important to note is how Foucault envisioned this kind of all-encompassing power. Rather than being something inherently restrictive—I know my mind first jumped to things like limiting access to contraception or abortion!—Foucault thinks of biopower as a type of power “that endeavors to administer, optimize, and multiply [life], subjecting it to precise controls and comprehensive regulations” (The History of Sexuality).

Maximizing life is a much more optimistic picture.

Do you think governmentality leans more one way than the other?

Continuity over time: Spheres of power, identity, and revolution

Now that we have a good understanding of Foucault’s ideas, we can start applying them to a real-life backdrop!

As I have thought more about Foucault’s ideas and compared them to my own learning, some critical questions have come up for me. Here, I’ll talk out my thoughts with you in the hopes that you feel inspired to make some connections to your own thinking and life!

What do Foucault’s ideas say about social or even cultural norms?

While reading up on disciplinary power, I came across this article on Medium (a writing platform whose mission is similar to TNT Lab’s: telling stories) that discusses what disciplinary power does in more detail. In this article, The Curious Philosopher describes how

through constant surveillance and examination, individuals are placed under a watchful eye, leading to self-regulation and internalization of social norms. This creates a sense of transparency and visibility, fostering a disciplinary environment where individuals feel constantly monitored. This constant scrutiny leads to individuals internalizing the gaze of authority, perpetuating a system of self-surveillance.

What stuck out to me was their commentary on social norms, where people seem to unintentionally submerge themselves in a world that puts them under the spotlight—and not in a great way. As we explored in the venn diagram earlier in this section, this system of surveillance changes and molds behavior, creating a body of people that act how they think they should be perceived. But who creates the standard, the guideline?

This past school year, I had the immense joy of taking a handful of humanities classes prior to “actually” beginning my major-related classes (speaking as a student nearing the end of her sophomore year who has just recently declared her college majors—Public Policy and Statistics!). Amongst those classes was an “Introduction to Political Theory” class—one of those classes that teaches about John Locke and the social contract. Locke’s social contract theory, if you’re not familiar, is his theory of how individuals form civil society, and then, ultimately, government.

According to Locke, prior to civil society, man was in a “state of nature,” where people had rights, but they were hard to protect, due to the lack of any enforcing structure. People leave this state of nature when they agree to give up their individualistic way of protecting their rights—i.e. murdering someone for touching their things—for an impartial power that makes rules and serves justice within the parameters of civil society. After civil society is formed, people can then form government in such a way as they choose.

The reason I bring up Locke’s social contract theory is actually to offer a countering voice—while this movement into civil society and then to government sounds peachy and smooth, there’s a lot to be said about how changing culture and rules affects people’s perception of their individual selves. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was one person who raised this idea.

Rousseau was a French philosopher who argued that Locke’s civil society created shallow people who lived in a state of constant self-comparison. Rousseau viewed the state of nature more as a paradise, where people had individuality and the natural instinct of pity: specifically, a willingness to empathize with people and help others. However, entering civil society snuffed out pity and replaced it with reason, where questions like “Does helping others benefit me?” permeated and alienation from each other began to grow. In this cut-throat world that Rousseau describes, maintaining authenticity becomes impossible. It’s oddly similar to the pitfalls of a disciplinary world, which is why I reach for Rousseau’s suggestion for how to leave behind the restrictions of social convention: see community as freeing rather than constraining!

This idea leads me to my next question, which is . . .

How does revolution fit within Foucault’s political theory?

If you don’t really see a connection between Foucault and revolutionary thought, I offer that discussing topics like mental reform and sexuality in a way that challenged status-quo ways of thinking is socially, perhaps even revolutionarily, significant.

To expand upon that thought, allow me to give you some additional context about who Foucault was. Foucault was an author who penned work critical to queer theory (e.g., The History of Sexuality), co-founded the Groupe d’information sur les prisons (a group dedicated to providing prisoners with humane conditions), was a frequent university lecturer, and endorsed the Iranian Revolution.

In short, there is plenty of continuity between Foucault’s work—and his actions—and revolution.

If that’s still not convincing, consider this: our friend from before, The Curious Philosopher, writes a how-to where

to resist disciplinary power, individuals can engage in acts of subversion and resistance. …Additionally, creating spaces for emancipatory practices and alternative forms of organization can provide avenues for individuals to escape the confines of disciplinary power.

Naturally, revolution stands out as one mechanism to execute the above, where rejecting current frameworks and building new ones offers hope of moving away from disciplinary power. These “alternative forms of organization” mimic Rousseau’s emphasis on building communities that advance liberties like freedom, suggesting that cycles of disciplinary power can, in fact, be broken away from.

And this actually isn’t as surprising as you may think it is. I personally find myself flashing back to our conversation on biopower, something seemingly intimidating but that Foucault presents as actually having people’s best interests at heart.

Disciplinary power, discourse, biopower, etc.—all of these concepts are shaped by people, and so people have the ability to affect the boundaries these concepts impose on society. Whether that’s through revolution or other ways of forming a social contract, people do have the ability to change how the world around them is organized. If you’d like an example, let’s consider the following—a case study, if you will.

How can an institution of disciplinary power like the education system be reframed to cultivate, rather than repress, individuality?

Changing the way we approach education, or the prison system, or behavioral health, or the plethora of other places where disciplinary power can exist, is, in my opinion, a form of revolution. How do we purposefully work to break from the norms of how institutions are organized in the present? This isn’t an easy question, but luckily, I have a nice toolbox of humanities learning to pull from 😉. For example, here is what my “Education in Multicultural Societies” course taught me:

Identity matters!!! Identity matters!!! Identity matters!!

I found that in situations where student-centered learning isn’t initiated, students:

- feel an increased sense of disengagement, which in turn corresponds with lower attendance and/or higher rates of dropping out (Oise 2003);

- are forced to seek recognition and support from outside institutions like community organizations due to schools being unable to provide sufficient intersectional spaces (Mayo 2018).

Long story short, when kids are taught in culturally-conscious environments where their intersectionality (how social categories like race, gender, class, and more overlap) can be voiced and appreciated, children have a resource and pathway to understanding why their perspective matters. This gives them power—power over their current learning and their future endeavors.

The famed Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire similarly describes how this kind of learning can free people.

If a similar methodology is adopted for other institutions beyond education, then perhaps people can start to chip away at the omnipresence that disciplinary power holds.

If you’re interested, check out this documentary on how students in one Arizona high school have been better empowered in their learning. This case brings into context the “fight” between social reform and social boundaries!

Where to Next?

Foucault’s Theories of Discourse and Power

Foucault and Narrative Transformation