“She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry,” a favorite documentary of mine, is the perfect film to watch to contextualize the era in which 13th Moon was founded in 1973.

It details both the elation and heartbreak involved when organizing a movement, hoping to provide an umbrella all while realizing that, in the end, you have little control over how the rain falls. Protesting is nothing if not dancing in the rain of blood, sweat, and tears. Sometimes it is actually dancing, and sometimes it is screaming at the top of your lungs, or creating art that breathes life back into the world.

If movement is to move, then it’s also to change. What would it mean for such movement for change to become part of women’s “ordinary” movement?

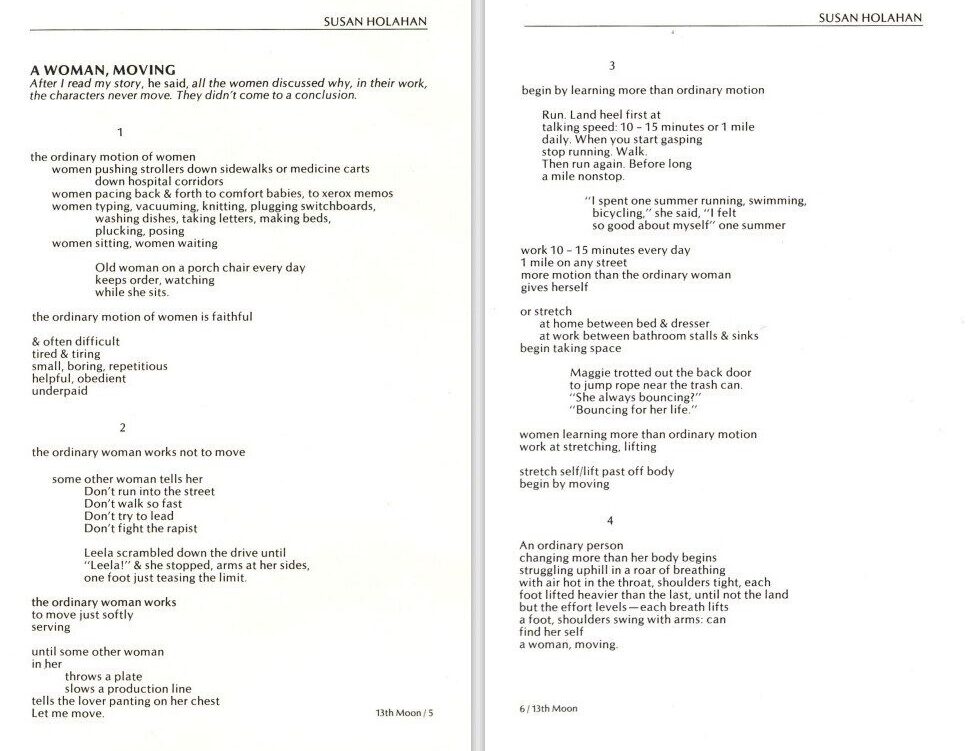

I am reminded of Susan Holahan’s poem, “A Woman Moving,” published in 13th Moon in 1978:

women learning more than ordinary motion

Susan Holahan in “A Woman Moving”

work at stretching, lifting

stretch self/lift past off body

begin by moving

Ten years before 13th Moon was first published, Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique (1963) gave a name to “the problem that had none.” This problem was the dissatisfaction that many women felt when they were subjugated to the sphere of the home. After the activism of the late 1960s recognized the pent-up rage around this problem, the question of the 1970s became how to channel it.

In the documentary, they praise Friedan for articulating a problem that many women felt they were alone in having, uniting women who were full of energy and giving amplification to female voices independent of their fathers or husbands.

However, the documentary also challenges Friedan, pointing out that by calling lesbian feminists “the Lavender Menace,” she was, ironically, silencing women who didn’t fit her narrative of femininity, thus continuing a cycle of oppression even as she was preaching liberation.

One of the protesters part of this “Lavender Menace”—a group of lesbian women who took up Friedan’s perjorative and wore it proudly—was Fran Winant.

Winant is pictured in the center of the photograph that is included as the thumbnail in the above video, and it is clear she is a proud member of the “Lavender Menace,” with her fist raised and a big grin on her face. The photo, taken at the Second Congress to Unite Women, documents the Radicalesbian takeover of a National Organization for Women (NOW) event, co-founded by Friedan.

“She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry” re-enacts the protest in the film, depicting masses of women standing up from the crowd, unbuttoning their shirts and coats, revealing the Lavender Menace t-shirts underneath. After they revealed their presence in the crowd, they linked arms in the aisles (effectively containing the crowd) and demanded acceptance in the movement.

Winant was also a contributor to 13th Moon. Her poem “Collected Works,” which appears in Vol. 2, No. 1 (1974), takes on themes of oppression, death, and the (im)materiality of one’s written legacy.

Check out Fran Winant’s (impressive) biography at the GLBTQ Archives.

13th Moon did not shy away from being a safe space for women-loving-women. Decades later, this reader couldn’t be more appreciative, especially with the current attempts to herd queer people back into the closet.

I can’t imagine how freeing it must have felt to read these works during the 1970s when liberation was first being openly discussed. To be discriminated against by society-at-large was to be expected, but in revolutionary movements, there is no place for bigotry or prejudice, as the ladies of the Lavender Menace would tell you themselves.

READ MORE: The Powerful, Complicated Legacy of Betty Friedan’s ‘The Feminine Mystique’

Similarly, while the Civil Rights Movement undoubtedly set the stage for the feminist movement, the documentary also highlights how the overwhelming majority of voices that emerged were primarily white. The question then was what to do with that information, and how to change it.

For some, the answer was revealed in the form of the printing press.

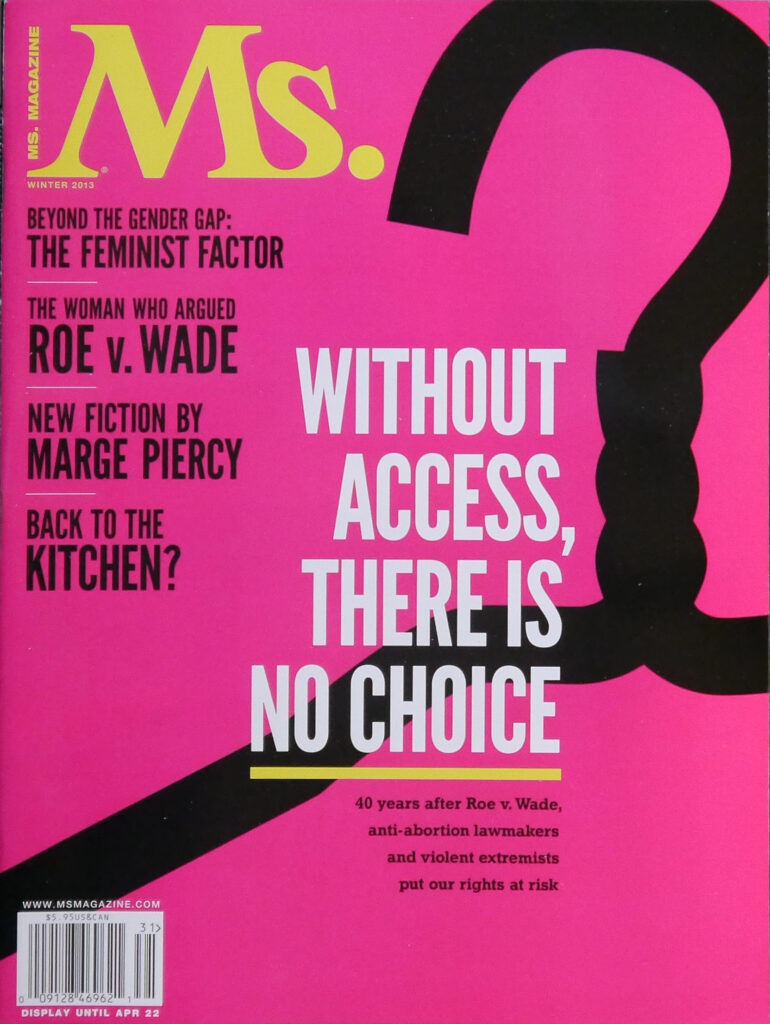

Ms. magazine, founded by Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes in 1971, gets most of the airtime when it comes to feminist publications of this era, considering it was the first magazine printed exclusively for women.

c

WATCH: Life and Legacy of Activist and Feminist Leader Dorothy Pitman Hughes

READ MORE: Gloria Steinem on Black Women: ‘They Invented the Feminist Movement’

WATCH: Gloria Steinem Explains Why You Should Be a Feminist

c

Image: Cover of the Winter 2013 issue of Ms. magazine (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Gloria Steinem’s My Life On the Road was the beginning of my own feminist journey. According to Steinem, experience is the best teacher, so the book is part-autobiography, part-political musings.

To me, the documentation of her experiences thus far, partnered with how they have shaped her political views, reads as a powerful manifesto. Her determination to secure her ability to live life to the fullest, despite preconceived notions of how people of her gender should behave, was a revolutionary act at the time, and it was revelatory to me at the time of reading as well. I highly recommend it to anyone and everyone.

c

Every year, my high school hosted an event called “A Day at the Museum.” My senior year, I went as Gloria Steinem, one of the leaders of the Second Wave feminist movement.

During my junior year, I went as British Suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, an activist in the First Wave of feminism.

Image © Jaylin Barrett, April 2019 (May not be re-used, copied, distributed, or remixed without prior permission from the author.)

Pitman Hughes’s and Steinem’s Ms. magazine may have been first, but it was far from the last publication to celebrate the work of women.

Soon after it appeared on the scene, a wave of smaller, independent magazines arose to amplify female voices that had been silenced for far too long. Among these publications was 13th Moon.

Part of the reason 13th Moon caught my eye is due to its mission of exclusively selecting works that were previously unpublished. Something about celebrating “ordinary women,” to use the language of Susan Holahan in her poem “A Woman, Moving”, was thoroughly compelling to me—and it only became more so as I read issue after issue.

As I read, I saw how the publication expanded from sharing pieces from across the U.S. to sharing them from across the globe. While their work still lives online, I hope this Rabbit Hole allows for their legacy to be recognized, seen, and felt by a new generation.

In fact, it is by writing this Rabbit Hole that I hope to play my own part in introducing 13th Moon to a new generation of readers. And, as I’m writing this at The Narrative Transformation Lab, I’d be remiss if I didn’t give a special nod to the issue that ensured to me this was the right “White Rabbit” to follow.

The cover of the 13th Moon: Narrative Forms issue shows Raggedy Anne placed next to a small statue of the Virgin Mary. The depiction of the doll, which I had myself growing up, next to the Virgin mother brought to mind how women are rarely allowed to be individuals. Women are either objects or saints. Rarely are women seen as individuals in our own right, without ideas of what we can do for others clouding how we are perceived.

The stories and narrative poems within this issue show how narrative-driven forms of writing are sometimes necessary to fully articulate the dichotomous, oftentimes paradoxical nature of womanhood.

Explore More!

Issues of Interest

Spring/Summer 1973

13th Moon: Working Class Experience

Volume 7, Numbers 1 and 2 (1983)

13th Moon Special Focus: Writings by Caribbean Women

Volume 12, Numbers 1 & 2 (1993)

13th Moon Special Focus: Italian Women Writers and Feminist Fiction

Volume 11, Numbers 1 & 2 (1993)

Speaking of Italian Feminism…

READ OUR RABBIT HOLE ON

(by Audrey Williams)

WHERE TO NEXT?

I. Women, Becoming

III. Women in Music: The Personal and the Political

IV. Celebrating Women Celebrating

CONCLUSION: Women Who Write